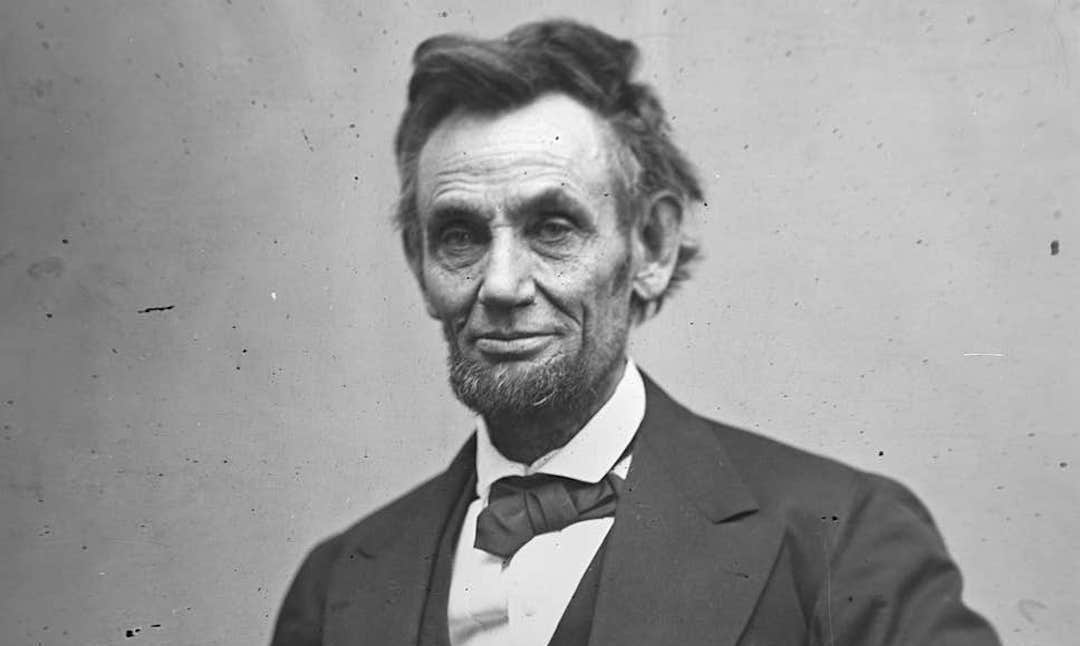

Abraham Lincoln’s Most Influential Speeches

Abraham Lincoln lived at a time when, according to historian and famed Lincoln biographer Doris Kearns Goodwin, speech-making prowess was central to political success, and the spoken word filled the air “from sun-up til sun-down.”

The following speeches by Abraham Lincoln represent a timespan of 27 years, during which Lincoln went from a relative unknown in Springfield, Illinois, to President of the United States.

Some of these speeches are famous; the Gettysburg Address and House Divided speech are famous Lincoln speeches of particular note. Some of them were delivered during the American Civil War; the First Inaugural Address and Last Public Address, among others, take these honors. And some of them speak of freedom and Lincoln’s views on American’s original sin, slavery; the Peoria Speech and Cooper Union Address draw heavy influence from these areas.

During the course of his life Abraham Lincoln is said to have given hundreds of speeches; a product of having started young and, of course, winning the American presidency. As Goodwin notes of early Abraham Lincoln speeches, “Lincoln’s stirring oratory had earned the admiration of a far-flung audience who had either heard him speak or read his speeches in the paper. As his reputation grew, the invitations to speak multiplied.”

Arguably one of, if not the, greatest ever president of the United States (much of which is attributed to the quality of his character), Abraham Lincoln’s speeches are as quotable as they are important. (If you’re interested in reading a collection of famous Abraham Lincoln quotes I have you covered.)

The below speeches by Abraham Lincoln are ten of his most influential.

Abraham Lincoln Speeches

Click on each of the Abraham Lincoln speeches below to read the background to it; where and when it was delivered, and how it was received by those who were in the audience, or simply scroll down this page to read each speech one-by-one.

- Lyceum Address (1838)

- Temperance Address (1842)

- Peoria Speech (1854)

- House Divided (1858)

- Cooper Union Address (1860)

- Farewell Address (1861)

- Address in Independence Hall (1861)

- First Inaugural Address (1861)

- The Gettysburg Address (1863)

- Last Public Address (1865)

Lyceum Address (1838)

Given when he was only twenty-eight years old, Abraham Lincoln’s speech at the Young Men’s Lyceum in Springfield, Illinois on January 27, 1838, is notable for being one of Lincoln’s first published speeches, as well as the speech that highlighted some of the ideas that he would bring to light in future speeches and, later, policy decisions.

Entitled The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions, Lincoln’s Lyceum Address centered on the threat posed by social disorder. “This topic was a conventional one for these lyceum meetings, where aspiring young men of the town tested their rhetorical skill and improved their elocution before their peers,” notes historian and biographer of Abraham Lincoln David Herbert Donald. “But Lincoln developed [his speech] in a highly personal way.”

While it’s been argued that the first half of Lincoln’s Lyceum Address employed standard Whig rhetoric of the day, the second half looked more toward the future; a future in which less stead is given to emotion in favor of cold-hard reasoning, or as Lincoln put it, carved “from the solid quarry of sober reason.”

Lyceum Address Excerpt

If the laws be continually despised and disregarded, if their rights to be secure in their persons and property, are held by no better tenure than the caprice of a mob, the alienation of their affections from the Government is the natural consequence; and to that, sooner or later, it must come.

Here then, is one point at which danger may be expected.

The question recurs, “how shall we fortify against it?” The answer is simple. Let every American, every lover of liberty, every well wisher to his posterity, swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their violation by others. As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and Laws, let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor;–let every man remember that to violate the law, is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the character of his own, and his children’s liberty. Let reverence for the laws, be breathed by every American mother, to the lisping babe, that prattles on her lap–let it be taught in schools, in seminaries, and in colleges; let it be written in Primers, spelling books, and in Almanacs;–let it be preached from the pulpit, proclaimed in legislative halls, and enforced in courts of justice. And, in short, let it become the political religion of the nation; and let the old and the young, the rich and the poor, the grave and the gay, of all sexes and tongues, and colors and conditions, sacrifice unceasingly upon its altars.

Temperance Address (1842)

Abraham Lincoln’s Temperance Address was given to the Springfield Washington Temperance Society in the Second Presbyterian Church in Springfield, Illinois on February 22, 1842.

While the Springfield Washington Temperance Society was not a religious organization, the location for Lincoln’s address meant that when the thirty-three-year-old started to advocate reason and kindness as a solution to alcoholism, he caused quite a stir with his audience. This aside, the speech showed a great early grasp from the future president of how to use rhetorical techniques in order to properly move listeners to his cause.

Temperance Address Excerpt

Although the Temperance cause has been in progress for near twenty years, it is apparent to all, that it is, just now, being crowned with a degree of success, hitherto unparalleled.

The list of its friends is daily swelled by the additions of fifties, of hundreds, and of thousands. The cause itself seems suddenly transformed from a cold abstract theory, to a living, breathing, active, and powerful chieftain, going forth “conquering and to conquer.” The citadels of his great adversary are daily being stormed and dismantled; his temple and his altars, where the rites of his idolatrous worship have long been performed, and where human sacrifices have long been wont to be made, are daily desecrated and deserted. The trump of the conqueror’s fame is sounding from hill to hill, from sea to sea, and from land to land, and calling millions to his standard at a blast.

For this new and splendid success, we heartily rejoice...

Peoria Speech (1854)

Perhaps the greatest antislavery speech of his career (or at the very least, the greatest antislavery speech of his pre-presidential career), Lincoln delivered the contents of his famed Peoria Speech twice; once on October 4, 1854 at the annual State Fair in Springfield, Illinois, and again on October 16 of the same year in Peoria, Illinois.

Presenting for more than three hours, in the Peoria speech Lincoln spoke of his objections to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Unlike those in favor, Lincoln did not believe that climate and geography would keep slavery out of the Territory of Nebraska, an area of land that consisted of the present-day states of Kansas, Nebraska, Montana, and the Dakotas.

During the Peoria speech Lincoln also “attacked the morality of slavery itself.” He argued that as slaves were people, rather than animals, they possess the same natural rights as all others. As Lincoln notes during the speech, “If the negro is a man, why then my ancient faith teaches me that all men are created equal; and that there can be no moral right in connection with one man’s making a slave of another.”

Peoria Speech Excerpt

The repeal of the Missouri Compromise, and the propriety of its restoration, constitute the subject of what I am about to say.

As I desire to present my own connected view of this subject, my remarks will not be, specifically, an answer to Judge Douglas; yet, as I proceed, the main points he has presented will arise, and will receive such respectful attention as I may be able to give them.

I wish further to say, that I do not propose to question the patriotism, or to assail the motives of any man, or class of men; but rather to strictly confine myself to the naked merits of the question...

House Divided Speech (1858)

Four years after his Peoria Speech, Lincoln found himself running against Democrat Stephen A. Douglas as the Republican candidate for U.S. Senate in the state of Illinois; the same Stephen A. Douglas who had presented the Kansas-Nebraska Act to the senate four years earlier.

Delivered on June 16, 1858 to more than 1,000 delegates in the Hall of Representatives of the Springfield, Illinois, statehouse, Abraham Lincoln’s House Divided speech was immediately considered too radical for a candidate for the U.S. Senate. Containing the famed “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” quote which Lincoln plucked from the Gospel of Mark 3:25, in which Jesus states, “And if a house be divided against itself, that house cannot stand,” the speech ultimately did Lincoln no favors in the short term, with friends, including Lincoln’s law partner, William H. Herndon, noting that while the speech showed great morality, it was politically incorrect. (Years later, Herndon is quoted as saying that despite Lincoln’s defeat in his race for the Senate, be believed the House Divided speech helped to make Lincoln president.)

House Divided Excerpt

Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Convention.

If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what to do, and how to do it.

We are now far into the fifth year, since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation.

Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only, not ceased, but has constantly augmented.

In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed.

"A house divided against itself cannot stand."

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.

I do not expect the Union to be dissolved -- I do not expect the house to fall -- but I do expect it will cease to be divided.

It will become all one thing or all the other...

Cooper Union Address (1860)

Originally slated to take place at Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, but quickly moved, thanks to a sponsorship by the Young Men’s Central Republican Union, to the newly-built Cooper Union in Manhattan, Lincoln famously did not make much of a first impression on his audience upon getting up on stage.

“The long, ungainly figure, upon which hung clothes that while new for the trip, were evidently the work of an unskilled tailor; the large feet; the clumsy hands, of which... the orator seemed to be unduly conscious; the long, gaunt head capped by a shock of hair that seemed not to have been thoroughly brushed out,” noted publisher George Haven Putnam, of Lincoln’s appearance.

Abraham Lincoln’s speech, on the contrary, made all the difference. Given on February 27, 1860, Lincoln spent a good portion of his Cooper Union Address taking shots at Stephen A. Douglas and his 1857 Kansas-Nebraska Act, nothing that he [Lincoln] had gone through the records of the Constitution Convention and early debates in Congress and it was clear that of the thirty-nine signers of the United States Constitution, twenty-one took votes demonstrating that the federal government had the power to control slavery within its territories, with a number of other men, including Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton, having also expressed leanings in this direction, though having not voted on it. (The Kansas-Nebraska Act argued that the territories of Kansas and Nebraska should be allowed to decide for themselves if they were to become slave states or not; a repeal of the Missouri Compromise of 1820.)

Further examining the Southern position on slavery, David Herbert Donald described Lincoln’s Cooper Union Address as “A masterful exploration of the political paths open to the nation,” and the journalist Noah Brooks exclaimed that Lincoln was “the greatest man since St. Paul.”

Lincoln's Cooper Union Address was quickly published as a pamphlet after the fact, with the speech being printed in a number of newspapers.

Cooper Union Address Excerpt

The facts with which I shall deal this evening are mainly old and familiar; nor is there anything new in the general use I shall make of them. If there shall be any novelty, it will be in the mode of presenting the facts, and the inferences and observations following that presentation.

In his speech last autumn, at Columbus, Ohio, as reported in "The New-York Times," Senator Douglas said:

"Our fathers, when they framed the Government under which we live, understood this question just as well, and even better, than we do now."

I fully indorse this, and I adopt it as a text for this discourse. I so adopt it because it furnishes a precise and an agreed starting point for a discussion between Republicans and that wing of the Democracy headed by Senator Douglas. It simply leaves the inquiry: “What was the understanding those fathers had of the question mentioned?”

Farewell Address (1861)

Praised for its humility, Abraham Lincoln’s Farewell Address was given as he was boarding a presidential train at the Great Western Railroad station, in Springfield, Illinois on February 11, 1861, to start his inaugural journey to Washington, D.C.

Along the course of his inaugural journey Lincoln’s train would make numerous stops, and he would speak at many of them, including at Independence Hall in Philadelphia.

Farewell Address Excerpt

My friends, no one, not in my situation, can appreciate my feeling of sadness at this parting. To this place, and the kindness of these people, I owe everything. Here I have lived a quarter of a century, and have passed from a young to an old man. Here my children have been born, and one is buried. I now leave, not knowing when, or whether ever, I may return, with a task before me greater than that which rested upon Washington. Without the assistance of the Divine Being who ever attended him, I cannot succeed. With that assistance I cannot fail...

Address in Independence Hall (1861)

Abraham Lincoln’s Address in Independence Hall was given on February 22, 1861 as Lincoln passed through Philadelphia on his inaugural journey to Washington, D.C.

Independence Hall, famous as the site in which the Declaration of Independence had been signed some 85 years before, was also one of several locations in which Lincoln’s body lay in state after his 1865 assassination.

Address in Independence Hall Excerpt

I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence. I have often pondered over the dangers which were incurred by the men who assembled here, and framed and adopted that Declaration of Independence. I have pondered over the toils that were endured by the officers and soldiers of the army who achieved that Independence. I have often inquired of myself, what great principle or idea it was that kept this Confederacy so long together. It was not the mere matter of the separation of the Colonies from the motherland; but that sentiment in the Declaration of Independence which gave liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but, I hope, to the world, for all future time.

First Inaugural Address (1861)

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln and James Buchanan, the outgoing fifteenth president of the United States, began the drive down Pennsylvania Avenue to the United States Capitol under the watch of sharpshooters and numerous companies of soldiers lining the blocked-off streets.

After attending the swearing in of his Vice President, Hannibal Hamlin, Lincoln was introduced to the stage to deliver his inaugural address and be delivered the oath of office by the eighty-three year old Chief Justice Roger B. Taney.

While some speeches of Lincoln’s are famed for their opening, Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address is more famous for its closing, which incorporated ideas from Lincoln’s one-time political rival, and soon to become his two-term Secretary of State, William H. Seward. Like much of the speech, which was written in Springfield, Illinois and shown to several of Lincoln’s friends and associates prior to its reading, Seward believed the closing of the speech to be too too strong. Despite making Seward’s, and others’, changes, reaction to the speech in the Confederacy was fierce, with the Richmond Dispatch saying that Lincoln’s speech had “inaugurat[ed] civil war.”

First Inaugural Excerpt

In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow countrymen, and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. The government will not assail you. You can have no conflict, without being yourselves the aggressors. You have no oath registered in Heaven to destroy the government, while I shall have the most solemn one to "preserve, protect and defend" it.

I am loth to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and heath-stone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

The Gettysburg Address (1863)

On November 19, 1863, Lincoln travelled to Gettysburg to dedicate the new Union cemetery. While Edward Everett of Massachusetts was the featured speaker, Lincoln was invited almost as an afterthought to give a few remarks. Everett spoke for almost two hours, then it was Lincoln’s turn.

At just 269 words, Abraham Lincoln’s speech at Gettysburg is famous for being one of the shortest, yet most powerful, speeches given during the American Civil War. Former congressman from Missouri James W. Symington noted of Lincoln during a Ken Burns documentary for the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS): “If I had my choice of all the moments to be present in that war period it would have been at Gettysburg during Lincoln’s delivery of his speech... to have seen him craft those beautiful words; those enormous, healing words, and then deliver them. They were for everyone, for all time. They subsumed the entire war and all in it; it showed his compassion for everyone; his love for his people. That’s where I’d like to be.”

Gettysburg Address Excerpt

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this...

Last Public Address (1865)

Abraham Lincoln’s Last Public Address would have been considered significant even if it had not been his last. Taking place just two days after the surrender of General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army, Lincoln’s speech on April 11, 1865 was given from the second-floor balcony of the North Portico of the White House to a cheering, jubilant crowd down below.

While it’s been argued that the majority of the speech wasn’t especially inspired—Lincoln himself was feeling more somber and aware of the task ahead, that of reconstruction, than his audience—the second half of the speech, in which Lincoln for the first time expressed his public support for black suffrage, ultimately sealed his fate.

After speaking the words, “It is unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man. I would myself prefer that it were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers,” John Wilkes Booth, the brother of famed actor Edwin Booth (of whom Lincoln had seen perform on numerous occasions), watching from the crowd outside the White House, is said to have vowed to his companion, “That means n— citizenship! Now, by God, I’ll put him through. That is the last speech he will ever make.” Three days later, Booth assassinated Abraham Lincoln.

Last Public Address Excerpt

We meet this evening, not in sorrow, but in gladness of heart. The evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond, and the surrender of the principal insurgent army, give hope of a righteous and speedy peace whose joyous expression can not be restrained. In the midst of this, however, He from whom all blessings flow, must not be forgotten. A call for a national thanksgiving is being prepared, and will be duly promulgated. Nor must those whose harder part gives us the cause of rejoicing, be overlooked. Their honors must not be parcelled out with others. I myself was near the front, and had the high pleasure of transmitting much of the good news to you; but no part of the honor, for plan or execution, is mine. To Gen. Grant, his skilful officers, and brave men, all belongs. The gallant Navy stood ready, but was not in reach to take active part.

By these recent successes the re-inauguration of the national authority – reconstruction – which has had a large share of thought from the first, is pressed much more closely upon our attention. It is fraught with great difficulty. Unlike a case of a war between independent nations, there is no authorized organ for us to treat with...

If you enjoyed this collection of the ten most influential speeches by Abraham Lincoln, please be sure to share it on social media, link to it from your website, or bookmark it so you can come back to it often.

If you’re interested in hearing more from me, be sure to subscribe to my free email newsletter, of which Abraham Lincoln (and the character traits and values in which he embodied) are a frequent topic of conversation. ∎